The Introduction of Photography in Race Record Advertising

1920’s Promotional Photography for Race Records

Photography provided the opportunity for musicians to represent themselves in the media. With the introduction of photographs, newspaper ads for race records changed from offensive caricatures to images that showed an element of pride for the singer.

Charley Patton was a star throughout his native Mississippi and much of the Deep South. But until 2003, virtually no one had seen a photograph of Patton that included more than a grainy version of his head. Patton’s photograph was discovered on a record dealer’s calendar in a stash of promotional materials found at the site of the F.W. Boerner Company in Port Washington, Wisconsin. F.W. Boerner was responsible for the mail order business of Paramount Records, an independent record company based in Wisconsin.i Paramount publicity was responsible for producing the sole known photographic portraits of many legendary musicians including Blind Lemon Jefferson and Blind Blake. The photographs had multiple promotional uses at Paramount between 1925 and 1932: on calendars, promotional books, and newspaper advertising.

Outside of live performances, the promotional photographs represented the first time many country blues musicians had the opportunity to visually represent themselves to the public. The Patton photograph may have been surprising to record buyers who had never seen him in person. His huge gruff voice belies his slight appearance shown in the portrait. His features appear to come from a mix of ethnic origins, his complexion certainly lighter than most of his fellow plantation residents in Dockery, Mississippi. Probably taken at a simple studio set, Patton sits in a chair looking directly into the camera with a stern expression on his face. Patton’s crossed legs and relaxed body language communicate confidence and control of the situation (far more so than the cropped version of the picture which only included his head). He chords his guitar in an unusual overhand manner.

Figure 1 - Charley Patton

It seems like playing music would be effortless for this man. Patton, notoriously unreceptive to direction in other settings, probably chose the pose and expression. He presented an image of himself as a master musician in control of his environment. The appearance was the result of conscious decisions. But, Paramount never used the full photograph in its newspaper advertisements or other widely distributed materials. Patton was denied the opportunity to use his representation in this medium on any large scale. Fortunately, this was not the case for many of Paramount’s other blues musicians.

The 1920’s were a transitional period for photography in advertising. Paramount and its competitors in the race record market for blues, jazz, and gospel records exemplify this. After 1925, Paramount, alongside Columbia, Vocalion, and Okeh, were regular advertisers in African-American newspapers including the Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier, Norfolk Journal and Guide, and Baltimore Afro-American. The Chicago Defender had national distribution and a circulation of over 200,000 African-American readers. A full page ad in the Defender would have cost $1000.ii The paper’s advertisers consisted mostly of local companies with products aimed at black consumers. The race record advertisements sit next to ads for skin whitener, sore leg healers, and other health aids. By the second half of the 1920’s nearly half of the images in advertisements were photographic. The same proportion applies to race record advertisements.

The introduction of photography into newspaper ads caused a change in tone for the advertising. Illustrations in early race records ads were caricatures of African-Americans, clearly offensive to modern eyes and surely representative of white advertisers out of touch with the black consumers of their products. Smaller companies did not have a national model to follow for marketing to African-Americans. Black consumers were largely ignored by national corporations. Unlike white consumers from different regions and classes, companies had not expended resources to learn what advertising was effective on consumers from black cultural backgrounds.iii

Photographs didn’t eliminate the cartoon depictions of blacks in race record advertising. But photography did provide the opportunity for the musicians to have a say in their own representation. This offset the message sent by the absurd illustrated images—that African-Americans were undignified objects of derision. Half-tone reproductions of photographs had been used in newspapers since 1904. By the 1920’s higher quality photo reproductions were common. Photography in newspapers became common in the late 1920’s.iv Some of the Paramount ads appeared with lesser quality half-tone reproduction so that the photographs unintentionally resembled drawings. Other advertisements use what appear to be engravings from photographs. Still, you can tell a photographic is the source by the simple appearance of dignity in the ad.

Why would the executives in charge of advertising choose to use the photographs when they seem to send a message that contradicts the rest of the art in the image? Photography was often used in advertising to convey sincerityv. But it seems that the presence of the drawings prevents the ad from conveying the “pure truth.” The record companies probably assumed that the photographs used consistently in advertising would generate loyalty to the artists who were often under exclusive recording contracts. The single goal inarguably shared by artist and record company was to sell records. The photographs were a shared method towards that goal. The drawn artwork was solely the product of white executives.

Paramount’s race record advertising generally followed a pattern. The advertising material was prepared by employee Henry Stephany, a local to Port Washington, Wisconsin where Paramount was headquartered until 1929. A Milwaukee advertising company, possibly the Meyer-Rotier company, would lay out the ads in cartoon form.vi A drawing would illustrate the song’s lyrics or at least the song’s title. A picture of the artist, usually with his instruments, would appear somewhere on the ad surrounded by an outline. The effect is of a musician storyteller projecting his tale. Paramount’s ads often contained more elaborate artwork than most of their competitors. Other companies used dramatic illustration, but less frequently and with simpler drawings. Some ads would include only the picture of the artist, the title of the song, and information regarding where the record could be purchased. Paramount was also unique in their pursuit of the mail order customer. Other companies listed local stores where records could be found. Paramount ads emphasized their ability to send records directly to homes for cash on delivery. The ads mirrored the larger 1920’s advertising culture encouraging a pleasure-minded ethic of convenience.vii Mail order was particularly important in reaching the rural consumer without access to stores selling records.

Columbia, a large company perhaps slower to change, used very little photography in their race record advertising before the 1930’s. Their ads included some of the worst depictions of African-Americans. The coal-black enormous-lipped confused figures barely resembled humans.

A notable exception was a 1925 full-page ad for Bessie Smith’s “Careless Love.” Smith appears in a large photograph looking like the glamorous performer she was in a jeweled headdress. It provides a stark contrast to the depiction of an African-American in the ad two years later for Smith’s “Mean Old Bedbug Blues.” Between 1925 and 1930 most Columbia ads resembled “Mean Old Bed Bug Blues.”

A notable exception was a 1925 full-page ad for Bessie Smith’s “Careless Love.” Smith appears in a large photograph looking like the glamorous performer she was in a jeweled headdress. It provides a stark contrast to the depiction of an African-American in the ad two years later for Smith’s “Mean Old Bedbug Blues.” Between 1925 and 1930 most Columbia ads resembled “Mean Old Bed Bug Blues.”

Figure 2 - Bessie Smith Columbia Advertisements

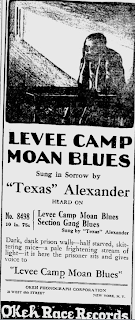

Vocalion and Okeh ads contained both drawings and photography but infrequently had the elaborate story pictures featured in Paramount ads. The other labels seemed split evenly between jazz, blues, and gospel records. Paramount’s roster was dominated by country blues artists. Ads for the white performers on these labels were generally plain, including a simple design with text and no illustrations.

Figure 3 – Okeh, Columbia, and Vocalion Race Record Ads

The artwork in most race records advertising was meant to be humorous. It resembles other cartoons and caricatures from the time period. The 1920’s were considered the “golden age of comedy,” and humor permeated the culture.viii The ads resemble syndicated cartoons like Hambone’s Meditations. These ads were created by white advertisers who likely never considered how potential black buyers would relate to the artwork.

Figure 4 - Hambone's Meditation, 1927

Paramount’s sole black executive, J. Mayo Williams, was responsible for bringing many of the recording artists and songwriters to the company. Williams was employed at Paramount until 1928. He had virtually no role in publicity and advertising. When asked about the advertising, Williams responded: “You never saw any language in those ads that was typically Negroid. They could have used a lot more Negro slang expressions than they did. They wrote the ads definitely from a white man’s point of view.” Williams’ comments seem to apply even more clearly to the drawn artwork than to the verbiage. Williams did have a role in producing the artists’ photographs. He coordinated periodic photography requests with Dan Burley, an employee of the Chicago Defender.ix This suggests that some of the early photographs may have been taken by African-American photographers. After 1928, photographs were most likely taken either at a Grafton, Wisconsin studio by photographer Walter Burhop, at the Theatrical Arts Studio, or at another studio in Milwaukee.x

Advertisements

The following sections analyze four Paramount advertisements that accompanied record releases between 1926 and 1932. I first saw each of these ads at JohnTefteller's Blues Images.

Blind Lemon Jefferson’s Black Snake Dream Blues

Wortham, Texas’ Blind Lemon Jefferson was the biggest male blues star of the 1920’s. He recorded over one hundred sides between 1926 and 1929. An itinerant traveler, Jefferson would travel to mostly rural areas where black workers congregated. Eventually Jefferson ended up in Chicago to record for Paramount. Like Charley Patton, Jefferson’s appearance does not seem to match his voice. Unlike Patton, Jefferson appears uncomfortable in his portrait. Perhaps this is indicative of the difficulty of a fat blind man trying to present a certain appearance, but never being able to see how it looks. According to contemporaries like Victoria Spivey and Tom Shaw, Jefferson regular dressed in suitsxi. He considered his clothing an important mark of distinction from the laboring classes that made up his audience. However, the tie in the picture is drawn addition of a clearly pre-Photo Shop artist. This was probably the decision of the Paramount publicity staff. It could be seen as an attempt to change Jefferson’s chosen image.

Of course, being blind, Jefferson was at a severe disadvantage when it came to visual self-representation. Some contend that he was not fully blind and the clear glasses worn in the portrait may support that notion. There is general agreement that Jefferson used guides and assistants, but was a remarkably independent man. He even worked as a professional wrestler before dedicating himself to music. Regardless of how much he could see, Jefferson was conscious of his image and worked at how he presented himself. Though he may not be totally successful, the effort can be seen in the photograph.

The Jefferson portrait was used for multiple promotional purposes including several newspaper ads. It was also provided to record buyers with an obviously forged autograph on the bottom from the blind and illiterate Jefferson as seen in Figure 5. The photograph appeared in the Paramount Book of the Blues, in record catalogs, and on other promotional material like dealer’s calendars.

Figure 5 - Blind Lemon Jefferson

Jefferson recorded “Black Snake Dream Blues” in 1926. The song was something of a sequel to Jefferson’s biggest hit from that same year, “Black Snake Moan.” The advertisement art seems to take a literal approach to illustrating the lyrics ignoring the sexual innuendo. Jefferson sings of his nightmare of black snakes getting into his bed. “Black Snake Moan” was about sexual longing, “Black Snake Dream” is about the fear of another man infringing on his sexual territory. The obvious sexual imagery of the lyrics doesn’t appear to be recognized in the artwork. The art communicates primarily a man afraid of snakes. The round-faced man lying in the bed bears some resemblance to Jefferson. This increases the importance of the photograph in the ad. The photograph proves the simple fact that Jefferson is a man and not a cartoon character. This may seem obvious, but this simple visual self-representation was absent before photography began appearing in the newspaper advertisements

Jefferson’s portrait is outlined in an oval and placed on the right side of the action. Two snakes at the bottom frame both the art and the photograph. When the viewer sees Jefferson in his suit with his guitar, the scene changes from one of a frightened black man in his bed unable to control his surroundings to one of a black man telling a story as entertainment. Most readers seeing the song’s title will be immediately aware of the sexual double entendre implied by the black snake and the picture makes it clear that this is Jefferson’s creation. Jefferson becomes a wordsmith, storyteller, and artist. The drawn figures become simply characters from his imagination, not the representatives of black life that they might seem to be with the absence of photography.

Figure 6 - Blind Lemon Jefferson's Black Snake Dream Bluesxii

Ramblin’ Thomas’ “No Job Blues”

“Ramblin’” Willard Thomas was a native of Logansport, Louisiana and something of a mystery to blues researchers for many years. He was discovered by Paramount talent scouts playing in Dallas where he was an associate of Blind Lemon Jefferson.xiii Recorded in 1928 at Paramount’s studio in Chicago, “No Job Blues” is a humorous tale of a man who loses his “meal-ticket” woman. Unable to find a job and with nothing to do with his time, he’s arrested for vagrancy. He ends up in jail wearing the standard black-and-white suit of a prisoner. He’s forced to work with a pick and shovel in the ice and snow. The song ends with his stated desire to find a new meal-ticket woman, so he won’t have to work.

The artwork illustrates the song’s lyrics with a prisoner sitting on top of the pile of rocks he is forced to break and fantasizing about a woman serving a meal. He wears the prisoner’s striped black-and-white suit. His dire expression does not communicate the humor evident in the song’s lyrics. The man bears no resemblance to Ramblin’ Thomas.

Thomas’ photograph is placed towards the upper right corner with a shield-shaped outline. Thomas is impeccably dressed in a suit. He looks directly at the camera with a big smile on his face. If the prisoner in the picture shows despair, Thomas’ smile and energetic pose show that his songs are for entertainment and pleasure. The lyrics seem decidedly not autobiographical. The lazy prisoner unable and unwilling to find a job is a character in a story. Ramblin’ Thomas is an entertainer holding his guitar trying to provide amusement with a story about an extreme reaction to the familiar circumstances of losing a woman and having a tough time finding work. His audience surely could connect with the character’s plight and laugh at the result.

Figure 7 - Ramblin' Thomas' "No Job Blues"xiv

As a musician and entertainer, Thomas fit into one of the accepted roles for blacks in the eyes of the white majority. The big smile may confirm the image as happy entertainer. But the photograph makes it clear that he is a sophisticated man, far different than the man with no job in the song. There are two disparate depictions of African-American men in the ad. The medium of photography allows Thomas to present his own self-image. The viewer can recognize which one contains elements of self-identification and is a depiction of a real person.

Skip James’ “22-20 Blues”

Skip James hailed from Bentonia, Mississippi. When he reemerged on the music scene in the 1960’s, blues researchers discovered a man with a remarkably enigmatic personality. He was an extreme individualist, extraordinarily proud of his musicianship and often disdainful of other blues musicians. According to biographer Stephen Calt, James liked to “give the impression of himself as a refined, civilized individual.”xv He recorded the piano and vocal piece “22-20 Blues” in 1931 at Paramount’s studio in Grafton, Wisconsin. The song was written as a response to a request for a song about guns to answer Roosevelt Sykes “.44 Blues.”

By 1931, Paramount was advertising much less frequently. The company was suffering in the Depression. The race record market as a whole was rapidly declining. Columbia would terminate their race record series the next year. Paramount had stopped advertising in the Chicago Defender after April 1930. The advertising art would have been used for more direct marketing efforts accompanying the release. This image is taken from the stash of Paramount art belonging to collector John Tefteller's Blues Images.

The “22-20” lyrics are quite violent and misogynistic, which was not unusual for blues songs of the time. James sings:

If I send for my baby and she don’t come

All the doctors in Wisconsin sure won’t help her none

And if she gets unruly and she won’t do

I’ll take my 22-20 and I’ll cut her half in two

The swagger with which the lyrics are sung make it seem that they are sung by a man familiar with a real world of violence.

The cartoon artwork shows an extreme caricature of a black man holding a pistol and staring through a window at a couple, presumably his girl with another man. The couple is on a date, smiling and drinking wine. The man holding the gun wears an outdated suit and an old hat, he’s clearly not as slick as the man inside. The cartoonist seems to see violence between blacks as a humorous situation.

The photograph of James is quite different than the portraits of the other musicians. This could be the result of James’ decisions, the work of a different photographer taking the picture, or perhaps a change in mentality with the Depression well under way. James is dressed more casually than any of the other musicians. He places his hand on an automobile in a gesture of ownership and possession. According to his recollections, James was a tough man in the twenties and early 1930’s. James described himself to author Stephen Calt as a gambler, bootlegger, and pimp—activities which were more typical a decade or so before James became a professional musician.xvi Though proud of his musicianship, this may be the image James chose to present in his photograph. This is an image bound to make whites uncomfortable, but a chosen self-representation far different than cartoon man of violence that may be its counterpart. James gesture of ownership of the car and glare at the viewer shows that he is not a man to be messed with, but he is a man of pride. This is almost the opposite of the cartoon figure staring through the window.

Figure 8 - Skip James' 22-20 Blues

Blind Blake’s “Bad Feeling Blues”

Blind Arthur Blake was a Florida native who spent most of the late 1920’s living in Chicago. He recorded there for Paramount between 1926 and 1932. Next to Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blake was Paramount’s best selling artist. He scored hits with “Diddie Wah Diddie” and “West Coast Blues.” The Paramount promotional portrait is his only known photograph. It is a very simple set, Blake, seated on a bench, faces the camera with a small smile. The portrait was used in multiple advertisements and the Paramount Book of the Blues. The Book of the Blues was a promotional volume sent to listeners. It contained photographs of many of Paramount’s artists with a brief (often inaccurate) biography. The Book of the Blues exemplified Paramount’s belief that photography could help engender loyalty to their artists and bring repeat record buyers.

Figure 9 - Blind Blake from Paramount Book of the Blues

The “Bad Feeling Blues” ad from 1927 followed the typical Paramount pattern of an illustration dramatizing the song’s lyrics with the picture of the artist to the side. The illustration shows a man being kicked out of the house by a woman holding a broom. He’s lost his hat and is running next to what look like fleeing chickens. The man is equated with the animals as objects to laugh at. The portrait of Blake appears in the lower left corner. The photograph is the familiar portrait of musician with guitar.

Unlike Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blake appears relaxed and comfortable in front of the camera. Blake would have had to deal with the same issue of not being able to see how he looked. Perhaps helped by a wife, Blake maintained a sophisticated appearance remarkably unlike the cartoon figure above him. Blake was described by contemporaries as a gregarious and friendly man. This comes through in the picture.

The cartoon drawing does not accurately reflect the song’s lyrics. The song tells of a man that cannot get along with his “high-brow girl” who he’d given money and taken care of. He decides to leave because of her mistreatment. Perhaps, the artists found it more humorous to depict an undignified black man fleeing witch chickens than to tell the story. But the picture of that black man is offset by the photograph of Blake. Blake presents himself as a man you would laugh with, not an object to be laughed at.

Figure 10 - Blind Blake’s "Bad Feeling Blues"xvii

Around the Country

While Paramount’s country bluesmen were performing throughout the South and recording in the Midwest, a renaissance was brewing in the Northeast. Men like Charley Patton and Blind Lemon Jefferson were not a part of the Harlem Renaissance. They never departed from their Southern roots. The country juke joints and even the urban house parties where they performed bore only the slightest resemblance to the culture of Harlem nightlife. Their music was what Harlem-based writer Alain Locke would have seen as important in terms of the early stages in the development of jazz, a pure folk form. Though he presumably would have seen the ads in the Defender, Locke seemed unaware of country blues as a popular commercial form.xviii

Despite the differences, there are many similarities between the self-representation in these photographs and the contemporaneous New Negro movement in Harlem. They shared the attribute of defining yourself and showing respect for black culture. Portraits of Paramount artists bear some resemblance to those taken in Harlem by photographers like James Van Der Zee. Van Der Zee used more elaborate studio sets and his subjects appear to be more elite and wealthier, but there are shared stances, expressions, and attitudes. The portraits cry out for these individuals to be judged on their own terms. They do not need the white man’s sympathy or approval; they have proud traditions and dignified culture of their own making.

Conclusion

Like the lyrics to many songs, the photographs of blues musicians are political in only a covert manner. By presenting themselves as the sophisticated artists that they were, they contradict some of the stigma of earlier artistic representations. They exemplify a form of self-representation which African-Americans were claiming in many forums at the same time.

The photographs are not revolutionary. They present African-American performers in traditionally accepted roles. But they represent a remarkable change from the cartoon images that preceded (and then coexisted with) the use of photography in race record advertising. The medium of photography allowed a diverse group of musicians to visually express their self-concepts. Paramount Records went out of business in 1933. Their promotional materials to that point provide an interesting evidence of a transitional period where photography contributed to African-Americans ability to represent themselves as creators of a proud culture. The performers are proud and diverse individuals, none of whom are the objects of scorn that African-Americans appeared as before the presence of photographs.

iThe results of this discover can be seen at Blues Images.

ii Van der Tuuk, Alex. Paramount’s Rise and Fall. Denver: Mainspring Press, 2003, p.80.

iii Ewen, Stuart. Captains of Consciousness. New York: McGraw Hill Book Company, 1976, p. 215.

iv Marchand, Roland. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920 – 1940. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

v Marchand 149.

vi Van der Tuuk p. 80.

vii Marchand 118.

viii Mintz, Lawrence. “American Humor in the 1920s” in Dancing Fools and Weary Bues. eds., Broer, Lawrence and Walter, John. Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1990, pp. 160 – 171.

ix Calt, Stephen and Wardlow, Gayle Dean. “The Buying and Selling of Paramounts (Part 3)” 78 Quarterly.

x E-mail from John Tefteller April 8, 2004.

Van der Tuuk, p. 106.

xi Calt, Stephen. Liner Notes for Yazoo CD 2057, Best of Blind Lemon Jefferson.

Davis, Francis. History of the Blues. New York: Hyperion, 1995, p.95.

xii Chicago Defender, August 27, 1927 p. 7.

xiii Wardlow, Gayle Dean. Chasin’ That Devil Music. San Francisco: Miller Freeman Books, 1998, p. 67.

xiv Chicago Defender, March 31, 1928 p.7.

xv Calt, Stephen. I’d Rather Be the Devil. New York: Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 60.

xvi Ibid, p. 75.

xviiChicago Defender, July 16, 1927 p. 7.

xviii Locke, Alain. The Negro and His Music: Past and Present.

Labels: advertising, blues, photography